Part of the series “SQL Techniques You Should Know”

If there is one SQL keyword that causes more fear than any other, it’s DISTINCT. When I see it in a query, I immediately start to worry about just how much work I am in for to ensure the correctness of that query. I start scanning for comments to describe why it is there, and if none are found, I know the query is probably going to be wrong.

I have seen DISTINCT used to hide bad joins, missing grouping, and even missing WHERE clauses. I have seen developers use it as a “fix-all” for data problems.

In this blog, I will look at the proper use and distinctly dangerous uses of DISTINCT and also show how you might test your query that uses DISTINCT to see what it is actually covering up.

And in every example, I promise a comment explaining why we need DISTINCT.

The good

First off, there are valid uses of DISTINCT. One that everyone can use is to find permutations of values that are unique in a table that don’t really merit their own table. For instance, in the AndventureWorks database, the PRODUCT table has a Color column that contains various colors of the products that the fine folks at the AdventureWorks shop sell..

For example, if I want to get a list of all the colors that are actually used in the table, I could write the following query:

USE AdventureWorks2025 GO SELECT DISTINCT Color --DISTINCT Color values use in the table FROM Production.Product;

This construct is used often and is perfectly legitimate. It’s one of the most basic things you can do in SQL and is a great way to get a distinct list of values from a column or set of columns. The following query answers the question “What color products were ordered on certain days?”:

SELECT DISTINCT OrderDate, Color

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

Sales.SalesOrderDetail.SalesOrderID

JOIN Production.Product

ON Sales.SalesOrderDetail.ProductID =

Production.Product.ProductID

WHERE Color IS NOT NULL;

Sure, the query is sort of nonsensical, but it’s just here to illustrate what you might do with DISTINCT. This pattern of using DISTINCT to remove duplicate rows from a result set is useful in certain scenarios.

Why not GROUP BY?

Sometimes you see a query like the following, which does technically return the same data.

SELECT OrderDate, Color

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

Sales.SalesOrderDetail.SalesOrderID

JOIN Production.Product

ON Sales.SalesOrderDetail.ProductID =

Production.Product.ProductID

WHERE Color IS NOT NULL

GROUP BY OrderDate, Color;

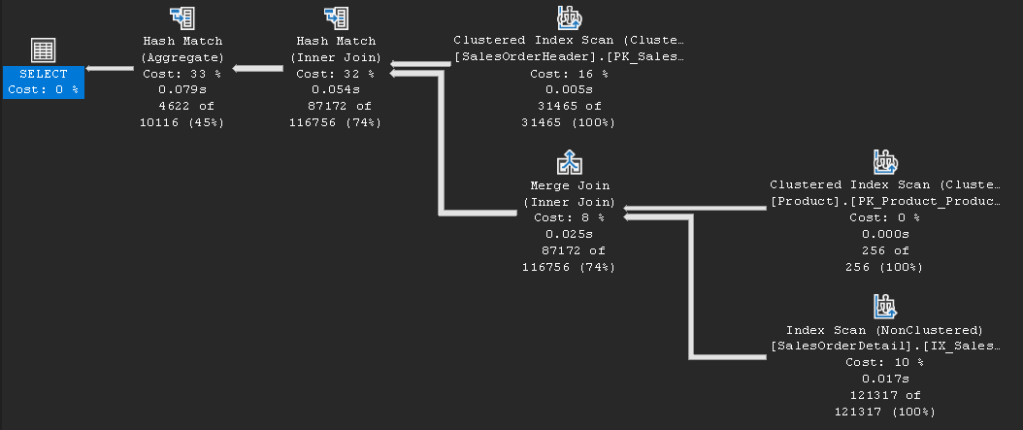

Both queries return the same rows, and they both have the same query plan:

But GROUP BY should always be used for grouping data, and DISTINCT when you need to see unique rows. The biggest concern when using DISTINCT is what are you distincting away. When you are trying to diagnose duplicated data, you will typically start with a GROUP BY with an aggregate, usually to show how many duplicates:

SELECT OrderDate, Color, COUNT(*) --Usually at least a count

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

SalesOrderDetail.SalesOrderID

JOIN Production.Product

ON SalesOrderDetail.ProductID =

Production.Product.ProductID

WHERE Color IS NOT NULL

GROUP BY OrderDate, Color

HAVING COUNT*) > 1; --and now cases of 1 or more

Use DISTINCT when you know there are duplicates that you need to output. It (plus those comments you are absolutely adding!) signals that you know there are duplicates, they are okay, and you need the set of values. Then use GROUP BY to aggregate, count, etc those duplicates.

This is why we shudder at the sight of DISTINCT

In the following query, see if you can easily see the issue?

SELECT OrderDate, Color

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID

JOIN Production.Product

ON Product.ProductID =

SalesOrderDetail.ProductID;

It isn’t a super complex query, so you probably see the issue, but I won’t give it away just yet. Grabbing a few rows from this output, you should be able to see pretty quickly that there is some data that is being duplicated.

OrderDate Color ----------------------- --------------- 2022-05-30 00:00:00.000 Black 2022-05-30 00:00:00.000 Black 2022-05-30 00:00:00.000 Black 2022-05-30 00:00:00.000 Black 2022-05-30 00:00:00.000 Black

So, like any good employee, let’s assume that these are correct results, so let’s add DISTINCT so we can move on.

SELECT DISTINCT OrderDate, Color

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID

JOIN Production.Product

ON Product.ProductID =

SalesOrderDetail.ProductID;

Did I mention that the version of the query without DISTINCT returns 3,817,239,405 rows. (It overflowed an int counting the number of rows so I had to use COUNT_BIG to count the results. The version of the query with DISTINCT? A “feels good” 10116 rows.

OrderDate Color ----------------------- --------------- 2023-02-09 00:00:00.000 Silver 2023-04-21 00:00:00.000 Silver 2024-01-07 00:00:00.000 Silver 2024-12-04 00:00:00.000 Silver 2023-03-04 00:00:00.000 Silver 2024-01-30 00:00:00.000 Silver 2024-12-27 00:00:00.000 Silver

I got a time value and a color value that were output. Sweet. But…is it right? Not even in the slightest (there are not 3.8 billion rows in this sales data! Testing by “feels” (an upcoming blog for sure) is always the first thing we do when writing queries that return a lot of data. You can easily feel that 3,817,239,405 rows of output is wrong. But the second output feels reasonable.

But that is why we don’t stop testing by feels. If you feel like you need DISTINCT, using GROUP BY with some aggregates can be a good way to verify your results

SELECT OrderDate, Color, COUNT(*)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID

JOIN Production.Product

ON Product.ProductID =

SalesOrderDetail.ProductID

GROUP BY OrderDate, Color

ORDER BY COUNT(*) DESC;

The output from this query outputs the same number of rows as the DISTINCT.. but look at those COUNT(*) values:

OrderDate Color ----------------------- --------------- ----------- 2025-03-30 00:00:00.000 NULL 9253295 2025-01-28 00:00:00.000 NULL 8365525 2024-12-30 00:00:00.000 NULL 8331380 2024-10-29 00:00:00.000 NULL 8263090 2025-03-30 00:00:00.000 Black 8156829 2024-06-29 00:00:00.000 NULL 7921640

Hmm, 9.25 million rows is a few more rows than we have in our Sales.SalesOrderHeader table to start with:

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail;

This returns: 121317

So yeah, always sanity check any query where you see a lot of duplicated rows, especially ones that you don’t really expect. In this case, you need to look at all of the code in the query:

SELECT OrderDate, Color

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID

JOIN Production.Product

ON Product.ProductID =

SalesOrderDetail.ProductID;

Then notice this join:

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID = SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID

This is true in every comparison that is not null (all of them in this case). So you get a Cartesian product between SalesOrderHeader and SalesOrderDetail, meaning for each of the 121317 rows of the SalesOrderDetail table (the number of rows you are expecting), you multiply the number of rows by the rows in SalesOrderHeader:

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader;

That returns 31465 and 121317 * 31465 gets us back to the 3,817,239,405 number from earlier.

So yeah, not good. Fix the JOIN criteria:

SELECT OrderDate, Color

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

SalesOrderDetail.SalesOrderID --fixed!

JOIN Production.Product

ON Product.ProductID =

SalesOrderDetail.ProductID

And now this returns 121,317 rows, and you can see that that matches the 121,317 rows in SalesOrderDetail.

And then you can DISTINCT that:

SELECT DISTINCT OrderDate, Color --Just need permutations of

--OrderDate and Color

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

SalesOrderDetail.SalesOrderID --fixed!

JOIN Production.Product

ON Product.ProductID =

SalesOrderDetail.ProductID;

Which returns 5031 rows, and you can test that with:

SELECT OrderDate, Color, COUNT(*)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail

ON SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID =

SalesOrderDetail.SalesOrderID --fixed!

JOIN Production.Product

ON Product.ProductID =

SalesOrderDetail.ProductID

GROUP BY GROUPING SETS( (OrderDate, Color),());

Which will return 5032 rows, with the extra row being:

OrderDate Color ----------------------- --------------- ----------- NULL NULL 121317

Summary

Every SQL programmer should know how and why to use DISTINCT. It is a very useful tool when you need it. It should never be used as a tool to eliminate duplicate data you didn’t expect to find in query results. It is meant strictly for when you know what you are expecting. You know there is some combination of column values that you want to get to see the output, and you know why they are repeated.

It is generally not a tool to find or remove duplicates in a set. Usually, duplication is not defined on an entire row. So if you have Customer 100, Name: Bob, ShoeSize 12; you may have Customer 100, Name: Bob, ShoeSize 12.5. DISTINCT won’t help you here if you need all three columns. Finding (and dealing with) duplicates is a topic that I will cover in a future post.

Leave a comment